Since the announcement of the National Automotive Industry Plan in 2013, the Nigerian automotive industry has witnessed an increased interest from several global automakers. As a result of the Plan as well as recent reforms made by the Nigerian government, PwC predicts Nigeria has a chance of becoming Africa’s auto manufacturing hub by 2050. However, the passenger vehicles market in Nigeria remains heavily dominated by imported second-hand cars, mainly due to the various industry challenges, including lack of access to auto financing. Could affordable auto financing schemes drive growth in Nigeria’s new passenger vehicles market?

This post formed a mainstay of a broader coverage article titled

‘Affordable auto financing essential for OEM success in Africa’, contributed by EOS Intelligence to ‘Guide to the automotive world in 2017’, Automotive World’s annual publication covering a gamut of articles by leading global automotive industry analysts and consultants. The report was published in January 2015.

Nigeria’s new passenger vehicle sales are far behind sales in countries such as Egypt, Algeria, and Morocco, despite the fact that Nigeria is the most populous country in Africa. With a giant share of nearly 80%, Tokunbo vehicles (local name for imported used vehicles) heavily dominate the Nigerian passenger vehicles market.

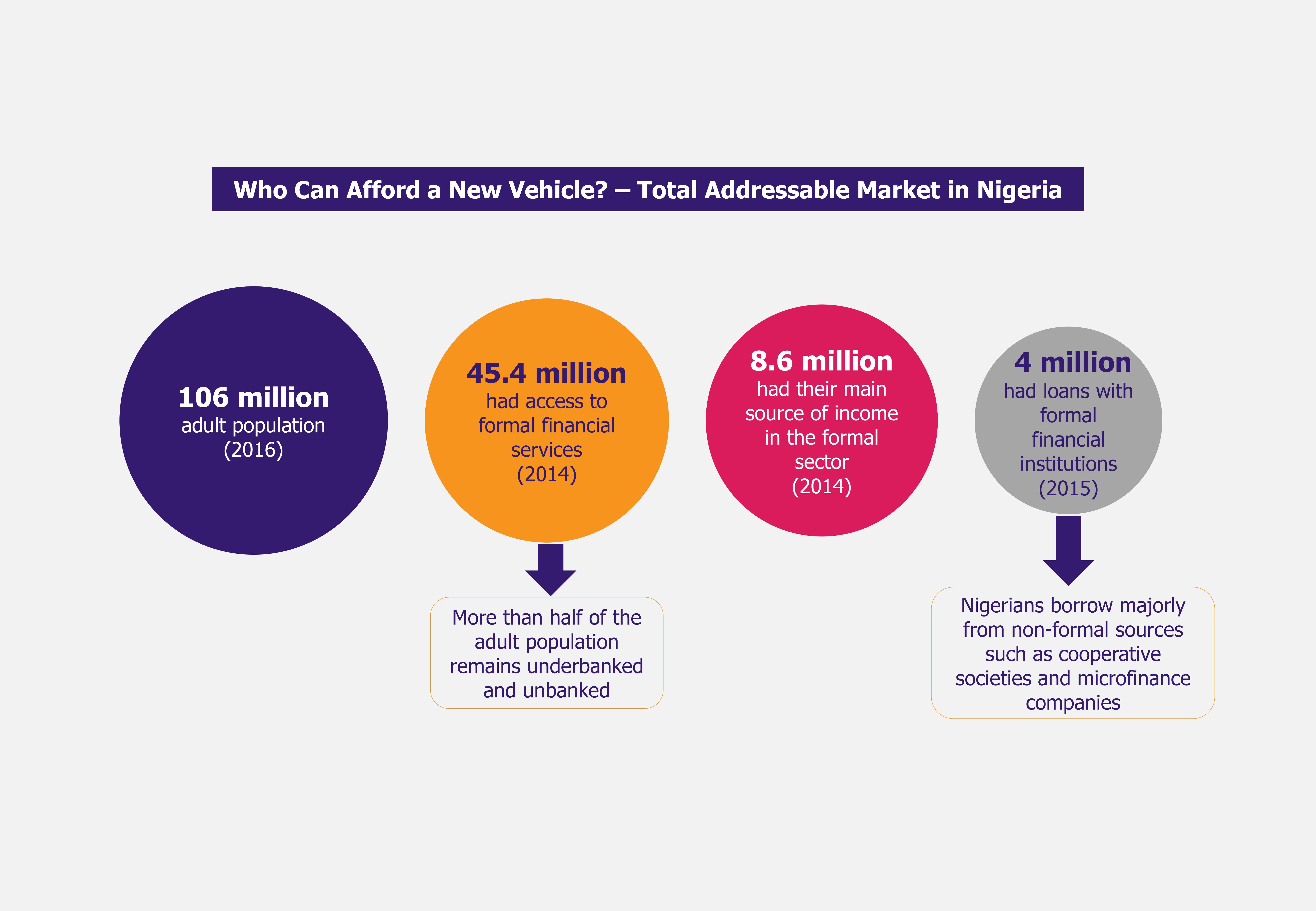

Although there is a plethora of industry challenges that range from lack of cohesive government policies to poor infrastructure, one of the major growth constraints at present is the lack of affordable auto financing. Due to the limited accessibility and expensive financing options, new vehicles remain out of the reach for most Nigerians.

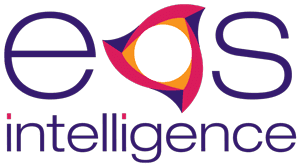

Currently, the cost of auto financing in Nigeria is exorbitant. Amid current economic environment and credit criteria, only a small segment of the population can obtain auto loans. Therefore, most Nigerians either buy used cars or save money over period of time to buy new vehicle for cash, stalling the new vehicle sales – retail customers accounted for less than one-third of all new cars sold in 2015.

This shows how lack of financing options is holding growth in a market segment with the highest growth potential. According to Lagos Business School’s research, an affordable vehicle finance scheme could boost Nigeria’s annual new vehicles sales to one million from 56,000 units at present.

EOS Perspective

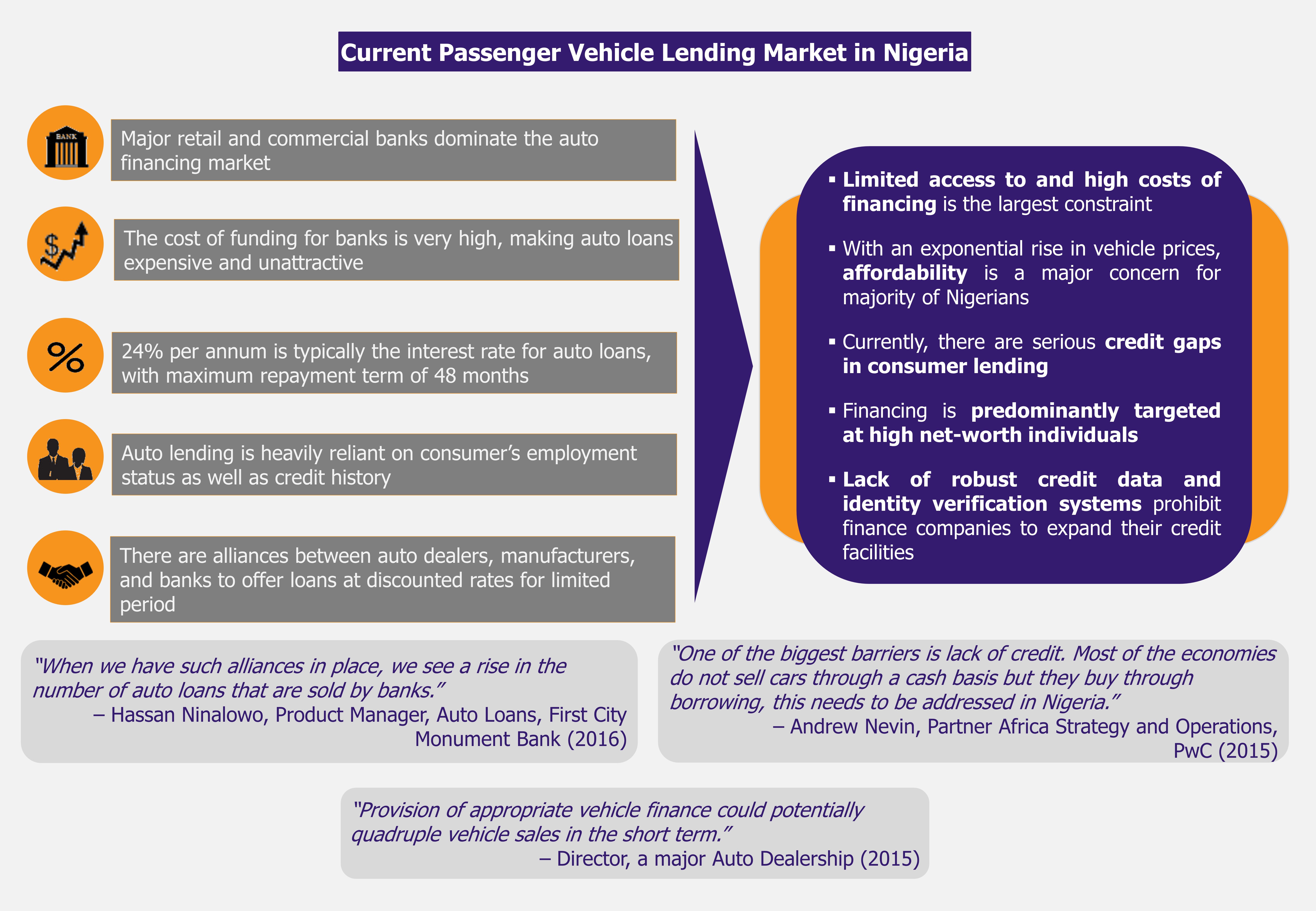

Although the National Automotive Industry Plan and recent government reforms managed to attract some FDI in recent years, the Nigerian passenger vehicles industry still remains heavily reliant on imported used cars. As the government plans to curb the country’s auto imports, as a first step, the industry stakeholders should plan policies that can make new vehicle ownership more attractive to mass consumers.

The current credit facilities offered by banks are unattractive to many consumers due to cost and credit terms. In order to fuel growth in local vehicle manufacturing and new vehicle sales, the industry, along with the help of CBN, should develop more affordable vehicle credit purchase schemes targeted at the mass middle class population.

Further, as majority of consumers simply have little or no credit history, the current lending models are not going take the industry growth any further. By leveraging on alternative credit data such as payment data from utility and telecom companies, lenders should look beyond credit scores to segment a new customer base of creditworthy consumers.

For vehicle manufacturers and dealers, there is a tremendous opportunity to move up the value chain by setting up in-house financing with the help of the right partners. By offering innovative auto finance solutions, they can push the demand for new vehicles, especially among millennial and emerging middle class first-time buyers.

Whether Nigeria is capable of becoming the next auto manufacturing hub for Africa, only time will tell, but with better financing options, it can surely boost new car sales and help the local automotive industry to progress.