1.9kviews

The concept of sharing economy has become a global phenomenon and after capturing several markets across Northern America, Europe, and Asia, it is now finding its way in Africa. The pre-existing sharing culture in several African countries makes this business concept gain good momentum across the continent. In addition to global companies, such as Uber and Airbnb, which have witnessed exponential growth in their limited years of business in this region, there are a host of home-grown players that are offering niche and country-specific services in this space. At the same time, sharing economy business does face a great deal of challenges in Africa’s complex markets. Safety concerns as well as limited availability and use of technology are two of the largest roadblocks for a thriving sharing economy business model. Although companies seem to find their way around these issues on their corporate drawing boards, the challenges are more intense and impactful in reality. Therefore, while the concept of sharing economy is likely to boom in the continent, it remains to be seen which companies manage to best adapt to local dynamics and thrive, and which players will fail in navigating the complexity of the regional markets.

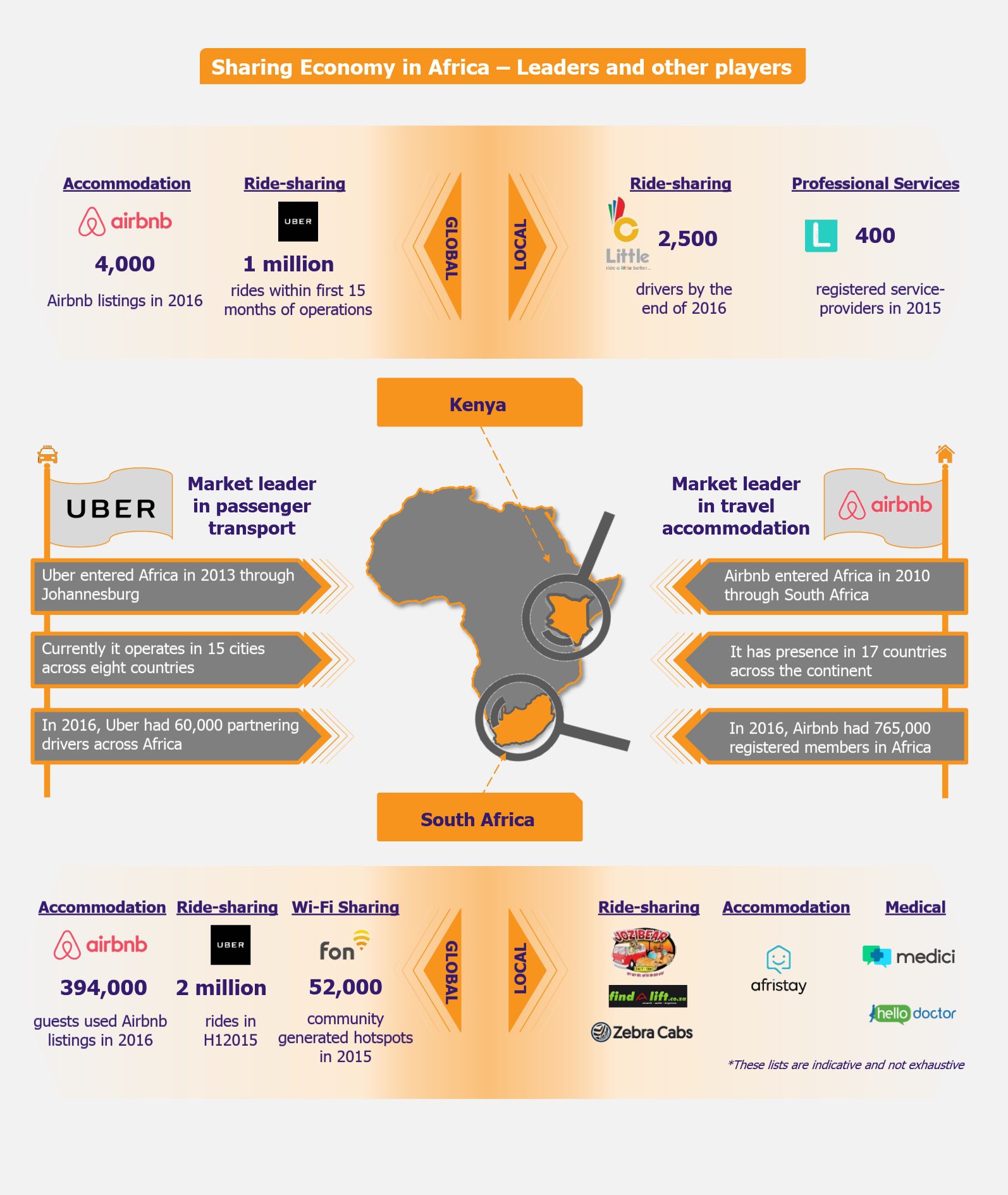

Sharing economy businesses have been growing at an accelerating rate globally with leaders such as Airbnb and Uber taking over their traditional hospitality and travel competitors and becoming the largest players in the tourism and passenger transport sectors, respectively. After gaining huge market in several mature economies, the asset-light collaborative economic model is now making its presence felt in Africa. With vast youth population and a growing middle class, several markets in the African continent offer a huge growth potential for companies operating the sharing economy model. In 2016, Airbnb alone witnessed a 95% rise in the number of house listings in the continent, which increased from about 39,500 in 2015 to 77,000 in 2016. Moreover, the number of users of its online platform reached 765,000 in 2016, witnessing a 143% y-o-y rise, and is expected to further expand to reach 1.5 million registered users by the end of 2017. Similarly, Uber, which entered Africa in 2013 through Johannesburg, has expanded into 15 cities across eight African countries in a span of just four years and has over 60,000 partnering drivers across the continent.

This remarkable growth is underpinned by a burgeoning middle class that is looking for (and increasingly can afford) convenient and reasonable solutions. Moreover, the sharing economy concept helps Africans bridge service gaps created by inadequate resources and infrastructure present in the continent. For instance, with increasing number of tourists and a limited number of high-end and mid-tier hotels or resorts, companies such as Airbnb are in a perfect position to fill such a demand-supply gap without much investment. In addition, sharing economy companies also help ease the unemployment and underemployment issues faced across several countries in Africa. The sharing economy model helps channelize a work stream for people who are unemployed or work in the informal sector, and provide them with a formalized platform where they can sell and market their services. Sharing economy is largely dominated by workers aged 18-34, which is also the age group largely affected by unemployment in Africa.

However, the key reason for the sharing economy model to have eased so well into the African lifestyle is the pre-existence of a sharing culture, which has been prevalent informally here for many years. Unlike in many developed regions, the concept of sharing economy is not new to Africa and the main task for global players entering this market was to formalize it through tech-based platforms. Therefore, despite being one of the least developed regions globally, Africa comes as a good fit to the sharing economy model. As per a survey conducted by AC Neilson in 2014, 68% of respondents in the Middle East and Africa region are willing to share their personal property for payment, while 71% are likely to rent products from others. These numbers are much higher in Africa than in Europe and North America, wherein only 54% and 52%, respectively, are willing to share their possessions for pay and even fewer (44% and 43%, respectively) are interested in renting others’ products.

While global companies are at a strong position to capitalize on this opportunity, there are a host of local players across the African subcontinent that are also looking for a share in the pie. Although these companies have come up across Africa, they are somewhat clustered in the more developed regions of South Africa, Kenya, Nigeria, and Uganda.

South Africa

South Africa

Being one of the most developed economies in the subcontinent, South Africa has openly embraced the global sharing economy phenomenon and has been the entry point into the continent for several leading international players such as Uber, Airbnb, and Fon. Uber has received great acceptance in South Africa with the first 12-month growth rates in Cape Town and Johannesburg superseding the growth experienced in other cities globally, such as San Francisco, London, or Paris (during their first year of operations). Uber provided 1 million rides in 2014, which was its first year of operation in South Africa, rising to 2 million rides by the first half of 2015. The company has also created more than 2,000 jobs in the country where unemployment levels are as high as 30%. Likewise, Airbnb boasts of similar growth in the country. In 2016, about 394,000 guests used Airbnb listings for their stay in South Africa, in comparison to 38,000 guests in 2014. During that year, Airbnb’s users generated US$186 million (ZAR2.4 billion) worth of economic activity in the country, of which about US$148 million (ZAR1.9 billion) was attributed to Cape Town, Johannesburg, and Durban. Fon, an unused bandwidth sharing company, also enjoyed success in the South African market and more than doubled its community hotspots from 21,000 (at the time of its launch in 2014) to 52,000 community-generated hotspots in 2015. Taxify is another global player in the ride sharing space. Launched in 2015, Taxify is an Estonian company offering similar services as Uber. The company has managed to acquire 10% of South Africa’s ride sharing market by offering 15% lower fares compared with Uber, while providing a higher driver payout (Uber takes a 20-25% cut from drivers while Taxify takes a 15% cut).

These international players are challenged by several local companies, which, despite being much smaller in size, are competing on both price as well as local expertise. In the ride sharing market, there are several smaller domestic players, such as Zebra Cabs, Find a Lift, and Jozibear. Similarly, in the accommodation sharing market, acting as a direct competitor to Airbnb is South Africa’s local, Afristay (formerly known as Accommodation Direct). The company has applied a country-specific approach and has succeeded in providing more varied and cheaper options as compared with Airbnb in South Africa. Having a single country focus, Afristay has close to 20,000 listings across 2,000 locations in South Africa. Airbnb on the other hand has 35,000 listings in the country.

Another emerging space of sharing economy concept adoption in South Africa has been seen in the medical sector, wherein players, such as Medici and Hello Doctor, are connecting patients with medical practitioners. Hello Doctor currently services around 400,000 patients in South Africa. Medici, which launched in May 2017 has partnered with the Hello Doctor and aims at connecting rural and less developed regions to remote access medical advice and consultations.

Kenya

Owing to a burgeoning middle class as well as an increasing access to education and the Internet, Kenya is a strong market for the digital sharing economy. Airbnb witnessed significant growth in Kenya, increasing its listings in the country from 1,400 in 2015 to 4,000 in 2016. The number of guests choosing to stay in an Airbnb accommodation have also expanded three-fold during the same period. Uber has received a similar response in the country, completing 1 million rides in its first 15 months of operations (beginning 2016), and having 1,000 drivers registered with them in the beginning of 2016. However, a local Kenyan company, Little Cabs, which is owned and operated by the country’s leading telecommunication players, Safaricom in partnership with Craft Silicon, a local software firm, is a stiff competition to Uber. The company, which began operations in July 2016, managed to acquire 2,500 drivers and 90,000 active accounts by the end of the year, owing to more attractive pricing and driver-payout in comparison to Uber. Moreover, it offers several services, which have not been introduced by Uber in Kenya yet. Having the backing of the leading mobile network operator, Little Cabs is attracting customers by offering them discounted mobile recharge along with trips, free Wi-Fi for passengers, and the option to process payments using M-Pesa – Safaricom’s mobile money service, which has two-third share in mobile market in the country. However, despite a smaller fleet size and less attractive services, Uber continues to be the market leader in Kenya for now, with a revenue share of about 30% (in comparison to Little Cabs, which has a revenue share of about 10%) primarily due its global brand value and first mover advantage.

Another newcomer to the sharing economy market in the country is Lynk, which aims at connecting service providers across about 60 categories to customers in Kenya. These include services such as plumbing, beauty works, tuition, or party planning. Having started operations in 2015, the company identified and recruited about 400 workers across 60+ service categories, who provided 800+ services to paying customers within its first year of operation.

All of that being said, the sharing economy concept has not had that easy of a ride in the continent and has faced one too many challenges on its way up. The main issue challenging the success of this concept has been the limited use of smartphones, which are inherent to this business model. While the use of smartphones in today’s time is taken for granted in most economies across the globe, this is not the case in Africa. In many cases, these service providers (especially drivers) are using smartphones for the very first time in their lives. Although the youth population is expanding in the continent, elevating the demand and use of smartphones, the numbers still remain extremely low – both at the consumers’ as well as service providers’ end. In 2015, only 24% of Africans used Internet on their mobiles and e-commerce penetration was mere 2%. This makes it imminent for companies looking to excel in the sharing economy space to provide training and workshops to help service providers adapt to and embrace the smartphone technology. Companies aiming to build a stronger position in the market over their existing competitors should also look at providing cost effective and easily accessible financing for the purchase of smartphones for service providers interested in registering in their sharing apps. In the African scenario, such a move would incentivize service providers to join the company’s sharing platform, potentially choosing it over other competitors present in the market, while the company would be able to expand its supply-end of the business by growing the registered service providers’ base.

The other issue that is key to operating in Africa is safety. Since the entire concept of sharing economy is based on trust, ensuring safety becomes a very important aspect in this line of work. Considering the high number of cases of theft and vandalism as well as weak regulatory system, African customers’ trust in service providers in their region is naturally lower than the western market customers’ trust in their local service providers. This impedes the service use growth and forms one of the largest barriers for sharing economy to reach its full potential in the continent.

In the transportation segment of the sharing economy market, the issue of safety is increasingly addressed by several players. To ensure safety of passengers, drivers undergo a rigorous background check that includes a multi-level verification. Companies also undertake innovative approaches to ensure only verified drivers work under the company logo in attempt to improve safety. In one such case, Uber introduced a ‘selfie protection’ feature, in Kenya, wherein a driver is required to take a selfie in the Uber app once in a while, before accepting a ride request from a customer. In case the photo does not match the one registered with the account, the account is blocked. In a market such as Africa, while safety precautions are a necessity, if marketed correctly, they can also be a differentiating and marketing factor. Along with general information and ratings, companies can also show driver’s verification details and training credentials on their app before a consumer selects a ride. In case of other services, they can also include details of the certifications undertaken by the service provider.

In addition to this, the limited use of plastic money – which is the main form of payment in sharing economy-based businesses globally – is another speedbump in the operation of such a business model in Africa. While several ridesharing companies are tackling this issue by introducing cash payments, it remains a limiting factor for companies whose services nature leaves a limited scope for introducing cash payments option, e.g. Airbnb.

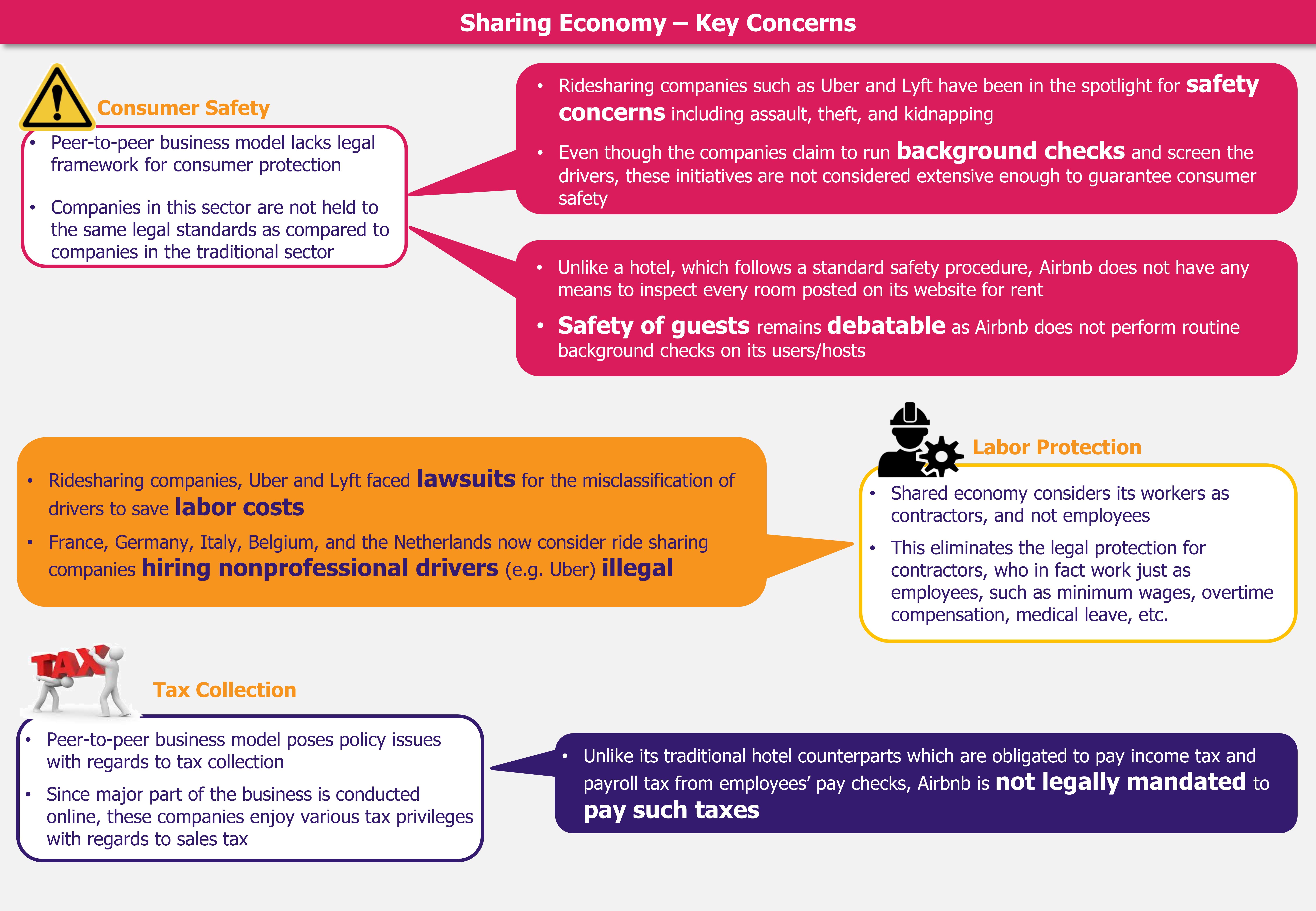

Regulatory barriers and outburst of traditional competitors is another challenge, however these issues are common for players across markets globally, though in various intensity. We have talked about it in more detail in our article in October 2016, Sharing Economy Needs Regulator Support. Companies such as Uber have had to face several regulatory roadblocks, the latest of that being a July 2017 lawsuit ruling recognizing Uber drivers as employees (instead of the company-preferred ‘driver partners’) as per South Africa’s labor laws. While the company does have plans to work around this ruling as it currently only applies to the seven drivers who filed the lawsuit, such issues have the potential to disrupt the companies’ smooth operations in the country. There have also been severe protests from traditional taxi companies and Uber has faced several safety-related problems with Uber drivers being attacked and cars being burnt in Kenya, as well as cases of smashed windscreens at railway stations in South Africa. To counter this, the company has posted security guards outside railway stations in Johannesburg for the security of the drivers.

EOS Perspective

While the concept of sharing economy seems to fit perfectly in the African lives, it does require the companies to follow a very localized approach accounting for specific regional dynamics in order to blend with the countries’ local fabric. While this gives an advantage to the local companies that better understand customer needs, it becomes difficult for them to match the scale of global leaders who have hefty marketing budgets.

Although sharing economy has largely captured the travel and passenger transport, with medical, education, and several other vocational services also seeing new businesses entering with sharing economy model, it is the crowd financing segment that might see the next boom in Africa. African region houses several dynamically emerging economies, with huge hunger for capital, and digital crowd funding platforms can help SMEs connect with potential investors, and help African start-ups with seed capital. In addition to basic investment, these platforms can also offer mentoring opportunities to small start-ups. While there already are a couple of companies, such as VC4Africa, that are operating in this space, crowd financing as a sharing economy business still has great potential to be tapped in Africa, especially beyond the Tier 1 cities of Johannesburg and Cape Town, where ideas are in abundance but there is lack investment and support.

—–

Originally published on EMIA on 21st December 2017.