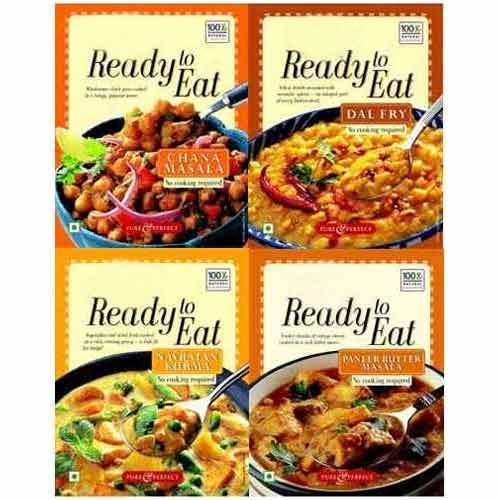

After a long day at work, a tasty meal is every hard working man and woman’s dream. But, cooking such a meal late in the evening – more of a nightmare. Enter ready-to-eat meals. Throw a packet in the microwave and your main meal of the day is steaming hot in under five minutes. What could be faster, tastier, more convenient and cheaper than that? Many options, Indians respond.

The healthy growth of ready-to-eat (RTE) consumer meals (i.e. microwavable pouches containing ready dishes) has become a success story across many countries, where lifestyles are getting busier, disposable incomes are increasing and women are becoming an integral part of the workforce. The RTE industry is taking several emerging economies in Asia by storm, as dynamic demographic and economic transformations occurring in many of these economies drive increased interest in convenience sought in matters of food by the region’s inhabitants. The trend, though, is of uneven magnitude, with rural communities largely remaining deeply traditional about home-cooked food, besides having very limited financial capacity to afford RTE products or a microwave oven. However, the growing preference for such meals is so strong amongst middle class groups, that, overall, the RTE segment across Asian markets has become an attractive area of opportunity for food companies.

RTE foods sector is one of the most dynamic growth sectors in the packaged foods markets across Asia, and on a global scale, Asian consumers exhibit the highest interest in RTE meals. A 2007 AC Nielsen study revealed that seven out of top ten markets with the highest propensity to purchase RTE meals are Asian countries, with Thai consumers emerging as the world’s biggest fans of RTE products.

RTE foods sector is one of the most dynamic growth sectors in the packaged foods markets across Asia, and on a global scale, Asian consumers exhibit the highest interest in RTE meals. A 2007 AC Nielsen study revealed that seven out of top ten markets with the highest propensity to purchase RTE meals are Asian countries, with Thai consumers emerging as the world’s biggest fans of RTE products.

Surprisingly though, India does not feature in the list of top 10 RTE markets. Unquestionably, the country does enjoy most of the RTE foods market growth prerequisites – fast developing economy, expanding modern retail channels, dynamically growing middle and upper class, rising nuclear family format, soaring participation of women in workforce, rapidly rising incomes and the growing reality of hectic lifestyles driving the demand for convenience.

So where is India in this picture? Why does its name not appear in the list of attractive RTE meals markets? Why do India-made RTE food products have a bigger market internationally than domestically? What are the challenges that RTE producers such MTR Foods, ITC Foods, Heinz India or Haldiram’s face in their home territory?

The fact is that although there is a market for RTE products in India, its size is modest and its growth is slowing down. AC Nielsen estimates the Indian RTE market growth slowed from 44.9% in 2010 to 28.1% in 2011 (reaching INR 506 crore, or about USD 110 million). In comparison, the Thai RTE market grew by 105% during 2005-2010, with a strong, upwards trend that is set to persist.

The reasons for such differing dynamics are many, largely due to cultural background and the Indian consumer’s mindset. Here are six key reasons why RTE foods producers have a difficult job in the Indian market, reasons, that might make them reconsider RTE expansion plans:

-

Traditionally, Indians are accustomed to hot fresh food served straight from sizzling pots, mainly because of easy and cheap access to domestic help and primary cooking ingredients easily available for purchase. RTE meals, despite their convenience, have a hard job competing with home cooked food.

-

Busy Indian consumers look for speed and convenience, and there’s plenty of options in the food services sector – countless cheap order-in and take-out options, that also offer great advantages over RTE meals, especially as these are freshly cooked, a factor of great importance to Indian consumers.

-

Unlike in many other countries, RTE foods in India are more expensive than most order-in and take-out options. This, paired with the preference for freshness, tends to put RTE products at a disadvantageous position.

-

Despite growth in modern retail format, majority of Indians still do their food shopping in traditional stores, which have limited space and interest in carrying novelties such as RTE foods (organised food retail is estimated to still account for only about 3-5% of the total retail market).

-

Considering the hot climate, Indian consumers tend to be reluctant to trust the safety of a ready meal that has been stored and transported out of temperature-controlled supply chain, especially given the largely inefficient supply chain management.

-

Some RTE meals, which do require cold storage, also fall prey to inefficient supply chain management and frequent power cuts, which lead to rise in production costs, in turn translating into higher RTE product prices resulting in lower demand for such products.

In spite of the many challenges, the Indian RTE market is growing, though at much slower rate than once anticipated. Indian attitude towards meal from a pouch is changing, with growing social acceptability to consume such foods and to prepare meals in the microwave.

Producers are optimistic, as the mere size of the potential customer base offer vast opportunities, even with slower y-o-y growth. But they also remain cautious, citing improvements in supply chain and distribution management, growth in modern retail format, continuous growth in consumers’ disposable incomes as the main changes needed to occur for the Indian RTE market to actually take off. However, given that many of these transformations have been occurring over the past years, perhaps these form just a secondary problem. Perhaps the key prerequisite for RTE market growth is the change in the Indian consumer’s mindset – change that is the slowest to occur and hardest to influence by producers.