In 2012, China unveiled its plan to invest in Central and Eastern European Countries (CEECs) through transregional platform called the 16+1 Cooperation framework. Since the launch of this framework, China has been proposing various policies of mutual benefit, making efforts to become an important trade and economic partner of the CEECs. While investments are welcome, several EU leaders and political experts in the region criticize such deals. They point at a threat of China’s growing dominance in the CEECs, as well as at China not keeping its promises made during the launch of this framework and negotiations of various deals.

China promises mutual benefits

The 2008 crisis brought worsened economic conditions to the CEECs, which have since been seeking capital to stimulate investment and facilitate higher economic growth, along with expanding exports beyond traditional European destinations.

Owing to China’s position as one of the largest economic power houses and due to the CEECs’ high trade deficit with China, the countries in this region showed interest in Chinese investments and opened their doors for potential avenues to increase trade with China. China too has looked for diversifying its export destinations and expanding its brands internationally, and CEECs could help it achieve just that. Chinese motivation to focus on CEECs has been fueled by two key factors: availability of skilled and cheaper workforce in CEECs (as compared to EU average) as well as China’s desire to gain stronger strategic influence in business and politics arena in the region as against the EU and Russia.

In this mutual interest, China and the 16 countries (Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Lithuania, Latvia, Macedonia, Montenegro, Poland, Romania, Serbia, Slovakia, and Slovenia) signed a framework named 16+1 Cooperation in Warsaw in 2012. At the outset, this framework aimed at deepening the multi-lateral economic ties, intensifying infrastructural and cultural cooperation, and capitalizing on the emerging business opportunities for both China and the CEECs.

The scope of cooperation was set to cover projects in CEECs’ infrastructure through investing in transportation systems by establishing new rail routes connecting the 16 countries with other parts of the world (Asia, Africa, and Middle East). China also intended to focus on capitalizing on green technologies, expanding export and import of goods, bringing new technologies for manufacturing sector, enhancing exchange programs for science, architecture, literature etc., and improving cross-cultural relations with the 16 countries.

Framework institutionalization raises a few eyebrows

In order to execute all the cooperation plans, the institutionalization of this framework in the CEECs became the first task to accomplish. It began with launch of Permanent Secretariat at the Chinese Foreign Ministry in China in 2012, followed by opening of Business Council in Poland (2014), Secretariat of Investment Promotion in Poland (2014), New Silk Road Institute in Czech Republic (2015), Center for Dialogue and Cooperation on Energy Projects in Romania (2016), Regional Center of the China National Tourism Administration in Hungary (2016), Coordination Mechanism on Forestry Cooperation in Slovenia (2016), Association for the Promotion of Agricultural Cooperation in Bulgaria (2017), China-CEE Institute in Hungary (2017), and few more.

Such institutionalization in the form of CEECs national coordinators, establishment of several secretariats, and a number of associations and industry organizations for individual states, became a crucial step towards enhanced political and economic relations of China and CEECs, and paved the way for further projects.

On the other hand, however, it left room for criticism. Some organizations, such as Institute for Security and Development Policy, Sweden, pointed out that establishing these institutions in a scattered rather than centralized way will deeply affect proper coordination and flow of information about all projects and initiatives within the framework.

Other voices of criticism, mostly from EU diplomats, warned about the fact that these institutions will limit accessibility to the information for the public. These institutions tend to work in line with the Chinese culture which differs greatly from cultural norms in European (and thus CEECs) organizations. In CEECs’ political culture (prevalent to various degrees across the European region), institutions are expected to actively and symmetrically communicate information to the public, providing room for public criticism and ensuring transparent procedures.

However, in Chinese political culture, public consultation and individual opinion are not given such importance. This leaves many EU leaders to ponder whether China’s intentions are to actually enhance the Sino-CEECs relations or to grow its dominance over the CEECs and act as it pleases behind the veil of its own culture providing an excuse for limited transparency.

OBOR and 16+1 framework go hand in hand

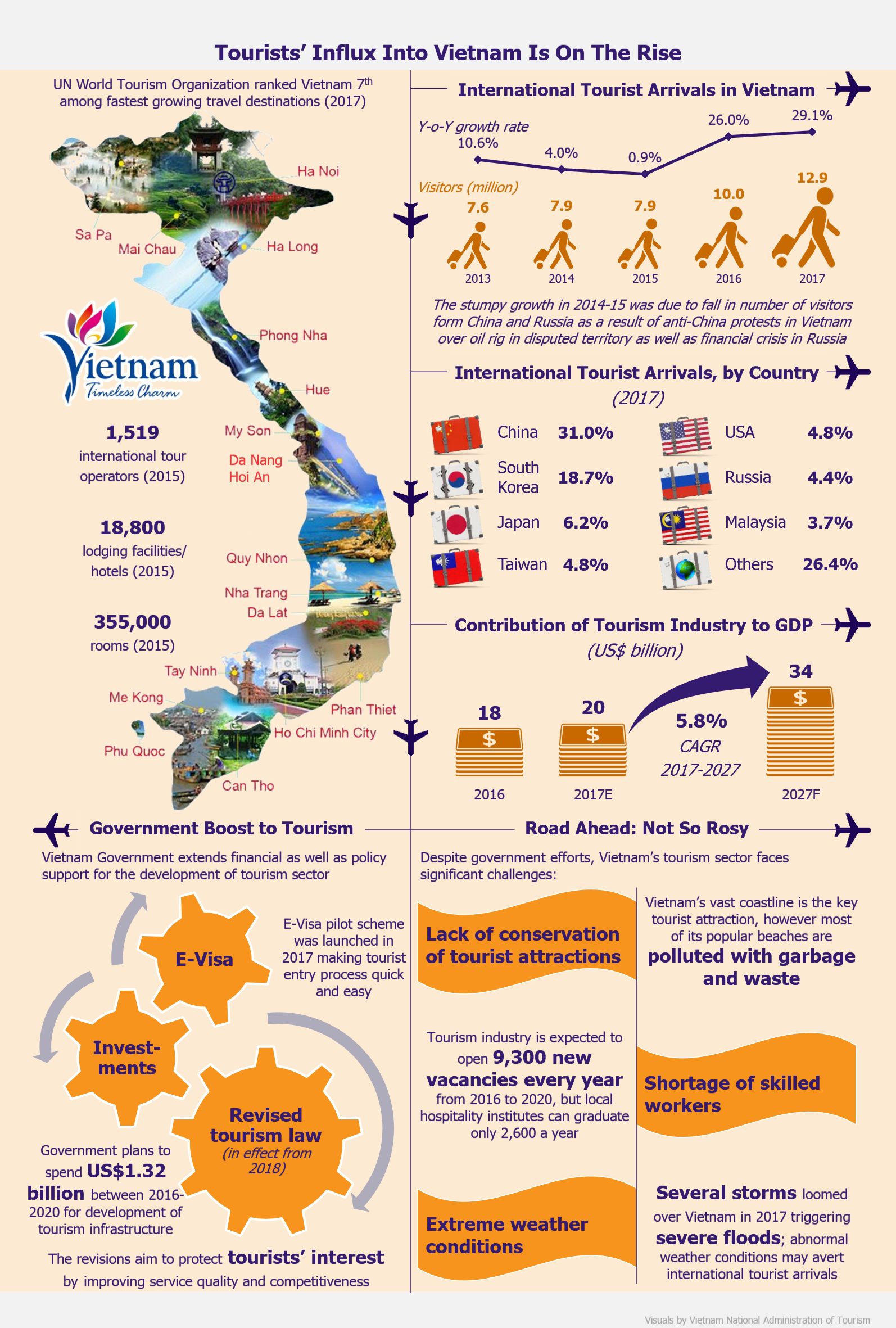

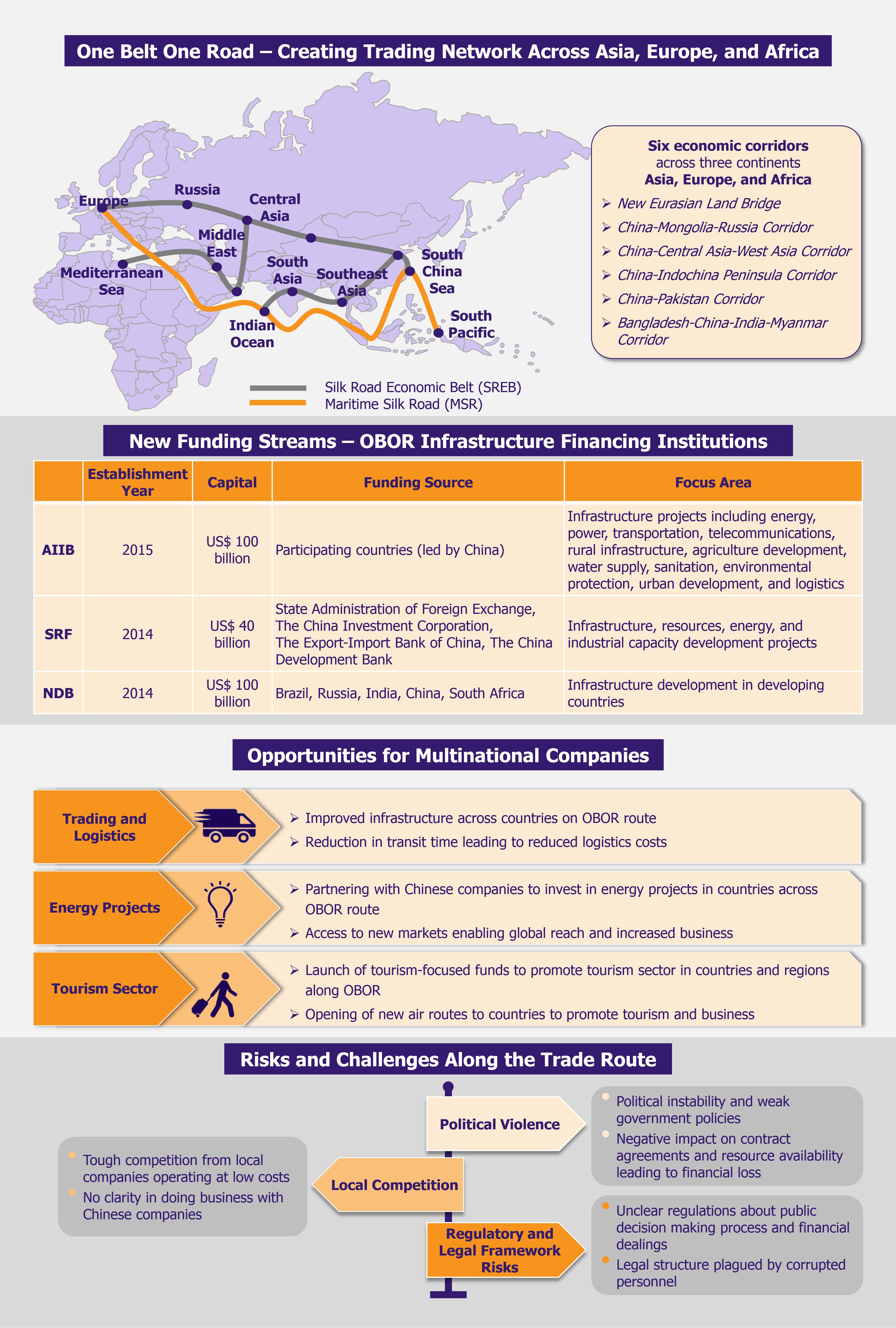

One of China’s major initiatives (and perhaps the only one so far considered to bring real benefit for both sides) is the One Belt, One Road (OBOR) project, launched in 2013 (we wrote about it in our article OBOR – What’s in Store for Multinational Companies? in July 2017). Under this project, China is ambitiously investing in developing one road connectivity, and this plan includes connecting the 16 CEECs with Asia, Africa, and Middle East. According to National Development and Reform Commission of China, Chinese investment in OBOR is likely to reach anywhere between US$120 billion and US$130 billion and with the external investments, it is expected to be totaling to US$600-800 billion by 2022. The success of OBOR is likely to impact the economies of CEECs though increased trade not only with China but also with other countries in Asian Pacific region.

The Balkans remain important in China’s plans

As part of OBOR, China has increased investment in infrastructure development in CEECs countries, with the initial focus on a few Balkan projects, especially in Serbia, with which China have always had excellent bilateral relations. The country appears to be the central hub in the Balkans for OBOR, both at an infrastructural and political level.

China started with a couple of agreements for infrastructure development with Serbia. These included China’s first large infrastructure investment in the region – construction of “Mihajlo Pupin”, the second bridge over Danube River in Belgrade in 2014 by China Road and Bridge Corporation (CBRC). The bridge shortened the travel time between Zemun on the south bank and Borca on the north bank of the Danube River from more than an hour to just 10 minutes. It also considerably reduced traffic problem on the first bridge. The project was received well by Serbia and taken as a good sign of China’s efforts to strengthen relations between the two countries.

China and Serbia came together for three more deals under the 16+1 framework, leading to total Chinese investment of nearly US$1.06 billion. These included US$715 million for construction of Kostelac power generation unit and expansion of coal-fired plant complex started in 2013, another US$350 million for re-construction of 34.5 km long segment of Belgrade-Budapest railway line, started in 2014, and undisclosed-value project of construction of Surcin-Obrenovac segment on Serbia’s E763 highway developed by China Communication Construction Company (CCCC) in 2017. All the three projects are likely to be completed by 2020.

Another flagship project, which involved Serbia and Hungary, was the construction of China-Europe land-sea fast intermodal transport route that was initiated in 2014 and became operational in 2017. With these infrastructural developments, China showed it delivered on its promises, and took steps to facilitate an enhanced exchange of goods with the CEECs.

Asymmetrical distribution of opportunities also causes criticism

The fact that all these projects were developed predominantly by Chinese firms, has been a cause for concern for western European leaders who criticized Chinese companies for seizing all opportunities and profits. The critics point out that if China and CEECs are coming together for such projects, the local companies should be able to benefit and be given opportunity to contribute skillset and technologies to local infrastructure development.

On the other hand, according to numerous experts, several countries, including Serbia, lack the technical and financial capacity required for such projects. China’s perspective should also be considered here – as China is already investing in the CEECs in the development of infrastructure, it is only logical (and natural) that it would prefer to engage own firms in order to help their business and take back some revenue from the projects.

China strengthens its foothold through financing initiatives

Chinese investments in CEECs are not only limited to the infrastructure sector, but also include certain financing initiatives in the form of availability of loans and funds. During the launch of 16+1 Cooperation framework, China announced a special credit of US$10 billion to the 16 countries to be used as preferential loans for implementation of common projects. Apart from that, in 2013, China together with CEECs launched a Sino-CEE investment fund of US$435 million, which aims at contributing financially to the sustainable economic development of CEECs.

Further, various banks and financial institutions, such as Bank of China, China Development Bank, China Export-Import Bank, and Industrial and Commercial Bank, have opened their branches in the region. While the official reason for this was to provide financial support and availability of funds to the CEECs, a relevant reason was also for China to expand the reach of these financial institutions’ brands in the European market.

Chinese investments grow in size and breadth

It is clear that China’s interest in CEECs has been growing, as exhibited through the sectoral breadth of investment initiatives and the variety of investment modes. Chinese companies are also pursuing the path of acquisitions and joint ventures with CEECs-based companies, the key example of which was seen in 2016, when Polish waste management firm, NOVAGO, was acquired by China Everbright International (Hong Kong). The deal was signed up at a value of US$144.3 million and was one of the largest acquisitions by a Chinese firm in the environment sector in CEECs.

While it is expected that such acquisitions can certainly bring benefits to the local entities involved in the deal (through capital and technology transfers, and easier access to the Chinese market), some concerns have been raised that an intensive Chinese-dominated M&A activity is not healthy for the local market dynamics.

The extent of these investments and acquisitions resulted in year-on-year increase in China’s outward foreign direct investment (OFDI) stock in the 16 countries. According to data from the Chinese Ministry of Commerce, the OFDI stock in 2010 in CEECs was estimated at US$0.85 billion and it reached US$1.97 billion in 2015, depicting an overall increase of around 130% in five-year period. Overall, Hungary was the leading recipient of FDI in CEE region with US$571.1 million, followed by Romania with US$364.8 million, and Poland with US$352.1 million in 2015.

The increased FDI in these countries is partially also a result of their interest in attracting Chinese investments even before the 16+1 cooperation framework came into picture. Poland, for example, being the largest economy amongst CEECs, started promoting itself with Chinese firms since the EXPO 2010 in Shanghai. For long, Hungary seems to have made a point to maintain good relations with China, even before other CEECs intensified multilateral relations with China. Hungarian government also made efforts to attract FDI, including from China, by proposing deals such as introduction of special incentives for foreign investors from outside EU or residence visa programs for bringing in a certain level of investment in Hungary.

Trade intensifies, though less than expected

Not only has there been growth in Chinese FDI since the yearly 2010s, but also the trade between China and the CEECs has grown progressively. According to Department of European Affairs at China’s Ministry of Commerce, trade between CEECs and China was estimated at US$43.9 billion in 2010 and grew to US$68.0 billion in 2017, showing a growth at a CAGR of 6.5% during 2010-2017.

While this might seem impressive, it must be noted that at the time of the launch of 16+1 cooperation framework, China promised to increase the trade value to US$100 billion by the end of 2015, which is far from the actual results even by the end of 2017. This again led to the criticism by the western European leaders over China’s ability (and willingness) to deliver on its promises, indicating lack of credibility in Chinese assurances.

On the other hand, the numbers do depict growth in trade between China and CEECs from 2010 to 2017 as compared to the previous years. According to Chinese Ministry of Commerce, China exports to CEECs were US$49.4 billion and imports from CEECs were US$18.5 billion in 2017, with an increase of 13.1% and 24%, respectively, from 2016. China’s exports to CEE concentrate on technology (with high-tech products from telecommunication, service sectors, and e-commerce sectors). CEECs supply agricultural products including fruit, wine, meat, and dairy products to meet the growing demand of the large population of China. Further interest in expanding imports of agricultural and dairy products by China can be expected, and an increased ease of exporting to China is likely to help CEECs to reduce their continued trade deficit in the coming years.

EOS Perspective

The rising investments of China in the CEECs have been under scrutiny since formalizing the 16+1 cooperation framework in 2012. Ever since the launch, China has been taking a range of initiatives that on the one hand worked towards development of the CEECs, but on the other hand gradually built its dominance in various markets and sectors in the region.

It is clear that such steps are taken by China in order to strengthen its political and economic foothold in the region. European leaders continue to remain skeptical over the intentions of China, which might also indicate the EU’s insecurity about China capturing strong hold over CEECs markets and building its dominance, which potentially might be able to overpower the EU’s influence in the region (especially in the Balkans out of which several countries are not EU members).

From the development point of view, initiatives such as OBOR, China-Europe sea-land express way, Belgrade and Budapest railway line, and even the mergers and acquisition deals, certainly bring advantages not only for China but for the CEECs as well, through much needed funding of infrastructure projects as well as through increased trade revenue.

Although it is of paramount importance for European watchdogs to keep an eye on the ongoing trade imbalance and growing Chinese ownership in CEE enterprises, it must be noted that acquisitions of CEECs-based firms by Chinese firms have largely affected the business in a positive way till now, thanks to influx of capital and the possibility to get the base to expand in Asian markets. Under this framework, despite its inherent issues and associated risks, steps taken by China for future development in the form of ongoing projects, especially in the infrastructure sector, have the potential to create more opportunities for the parties involved to strengthen cross-regional trade and hence create a (almost equal) win-win situation for both China and the CEECs.