For food delivery, e-commerce was an option before COVID-19, but as the pandemic unfolded, it became the preferred way to take customers’ orders. Restaurants were shut down for indoor dining, so customers turned to cloud kitchens to order and enjoy restaurant-like food without having to step out. The ease of having high-quality food delivered right at the footstep has instigated people, now more than ever, to order in. The pandemic has accelerated the cloud kitchen business, causing a paradigm change. Customer- and technology-driven cloud kitchens reflect a business model that will be adopted, sooner than later, unanimously by players in the food and restaurant service space.

The global cloud kitchen market was valued at close to US$ 52 billion in 2020, with the APAC region accounting for more than 60% of the global market share. Rising disposable income and increased use of smartphones have been driving the increase in online food delivery services (on which cloud kitchens depend), but it was not until the pandemic entered the scene that cloud kitchens really gained traction as restaurants and other eateries closed down.

COVID-19 accelerated the ascent of cloud kitchens as people used food delivery services much more frequently than before the pandemic. The growth was further favored by the trivial need for dine-in space due to social restrictions.

Everyone wants a piece of cloud kitchen on their menu

While China, India, and Japan are the key markets driving the growth of the cloud kitchen market in the region, the market in other countries is also witnessing significant growth rates. For instance, JustKitchen, a Taiwan-based cloud kitchen operator established in March 2020, has 14 “Spokes” (smaller kitchens for final meal preparation and packaging) and one “Hub” (larger commercial kitchen where earlier stage food preparation takes place) across the country. The company further plans to expand both domestically (by having 35 Spokes and two Hubs in Taiwan by the end of 2021) and internationally – it opened its first overseas kitchen in Hong Kong in June 2021 and plans to expand further in Singapore, the Philippines, and the USA. Another player, GrabKitchen, owned by Singapore-based online-to-offline (O2O) mobile platform Grab, which opened its first cloud kitchen in Indonesia (in 2018), now has operations in Thailand, Vietnam, Singapore, Myanmar, and the Philippines.

Restaurant chains are the primary adopters of the cloud kitchen concept. The pandemic has made India-based QSR chain Bercos realize that it is important to include deliveries as part of the business plan, because of which it is planning to launch three new cloud kitchen brands in the western and southern parts of India. Another Indian multi-brand cloud kitchen player, TTSF Cloud One, looks at opening 150 cloud kitchens by 2022. They aim to invest between US$ 3.3 million to US$ 4 million in the project through a combination of owned cloud kitchens, retail stores as well as franchised stores, and franchised cloud kitchens.

Owing to corporate strategy and global restructuring, the Philippines-based fast-food restaurant chain Jollibee Foods announced (in May 2020) that it would spend US$ 139.4 million on building its cloud kitchen network.

Global food chains are also partnering with local players to increase their outreach in the cloud kitchen ecosystem – in 2020, Wendy’s, a US-based fast food restaurant chain, entered into a joint venture with Rebel Foods, an Indian online restaurant company, to open up 250 cloud kitchens across India. This is a strategic move for Wendy’s as the company will get immediate access to scale rapidly across the country because of Rebel Foods’ existing network of cloud kitchens. Furthermore, Rebel Foods recently announced that the company plans to add another 250-300 locations to its repertoire across Southeast Asia, West Asia, and the UK via partnerships.

With the cloud kitchen concept growing at an astronomical rate, players, especially in nascent markets, are also looking to scale up rapidly. CloudEats, a Philippine-based cloud kitchen, plans to expand its reach further within the country (it currently has five cloud kitchens domestically) and other countries with the highest online food delivery penetration across Southeast Asia. Bangladesh-based cloud kitchen and digital food court player Kludio launched Kitchen-as-a-service to help restaurateurs, home cooks, and virtual brands expand with no upfront investment, and FoodPanda Bangladesh, in July 2020, announced that it would be launching 30 new cloud kitchens (in a period of 6 months) across the country.

Cherry-picked business model served on a silver platter (well, almost)

Cloud kitchens present a sea of prospects for both food and restaurant industry players as well as other adjoining sectors. They represent the potential of a tech-enabled business model for the restaurant and food delivery industry, where operational jobs in the kitchen will be handled by robots and deliveries made by drones. Another opportunity is for restaurants that would like to expand their geographical reach but are incapable of opening another dine-in place. With a cloud kitchen in place, they can access new markets via delivery only. Restauranteurs can further use it to their advantage by experimenting with new food items with relatively no investment and low risk. Last but not least, the mid and large-sized restaurant chains, which thrived on the dine-in concept (before the pandemic), will be quick to jump and adapt (some players have already ventured into this space) the cloud kitchen model to capitalize on the growing food delivery business. Furthermore, new players entering the restaurant and food business can take this as an opportunity to pan the layout of their premises in a way that space is efficiently optimized to adjust both the restaurant layout as well as the delivery service.

But it is not all smooth sailing. With a large number of cloud kitchens sprouting, the competition will be fierce in the coming years. Furthermore, with only so many food delivery platforms to support the already crowded cloud kitchen market, they are easily exploited by food aggregators. Not only do aggregators charge a high commission (ranging between 25% and 40%), the ratings for cloud kitchens on these portals (for a cloud kitchen) play a massive role in influencing other customers and affect the brand value.

EOS Perspective

Unlike restaurants, a cloud kitchen offers no dine-in facility and relies solely on online orders. The delivery-only model has its limitations, especially when it comes to customer experience. And a slowdown in dine-in style is indicative that restaurants are moving forward and looking to enter this space. Therefore, a hybrid model where cloud kitchen and dine-in concepts integrate is most likely to rise in the future.

The restaurant industry is recovering from the coronavirus crisis and adjusting to the fact that a pandemic could shake the entire foundation of the sector which was once based on dining in. But now, with more and more people ordering in, the burgeoning cloud kitchen space represents a sprouting new business model. In the near future, smaller brands are most likely to embrace a cloud kitchen network model, whereas the hybrid business model (combining physical stores and cloud kitchens) will work best for the larger and established brands. For instance, in July 2020, Thailand’s fast-food restaurant chain, Central Restaurants Group (CRG), which currently operates 1,100 fast-food outlets nationally, announced that it would open 100 cloud kitchens across the country in the next five years to strengthen its food delivery business. Moreover, as social distancing becomes the norm (wherein restaurants are forced to maintain sizable distances between tables) and preference for eating out reduces, the dine-in spaces across restaurants are also likely to shrink.

In the long term, the concept of cloud kitchen seems practical and a plausible winner, however, its success hinges entirely on the growth of the food delivery market. Before the pandemic, in 2017, APAC led the global online food delivery market with a share of 52.1% and market revenue of US$ 34.31 (the region was anticipated to contribute a revenue of US$ 91.0 billion and a share of 56.2% by 2023). Post-pandemic, these figures have multiplied and present a space that exudes growth potential. For instance, in Southeast Asia, the food delivery market grew 183% from 2019 to 2020 (in terms of gross merchandise value) owing to changing consumer behavior (towards how they consume food) and the ease of ordering due to digitalization. Moreover, the growth in the food delivery sector is expected to continue.

Food aggregators have been active in the cloud kitchen space even before the pandemic hit. Their value proposition of acting both as a supplier (wherein it allows independent cloud kitchen players to use its platform while charging them on a revenue-sharing model) and operator of the platform puts them in an interesting position, where they have control, to a certain extent, of business functions of other players. Food aggregators may likely dominate this space in the long run.

The metrics of the food and restaurant service industry have changed as businesses evolve continuously. With concepts such as cloud kitchen, the sector has become consolidated, wherein multiple establishments work under a single roof. In a nutshell, cloud kitchens are here to stay as they display substantial growth potential, provided players revisit their business strategies and rethink the right hybrid business model (such as merging with a large brand to expand into cloud kitchen space, among others) in order to thrive.

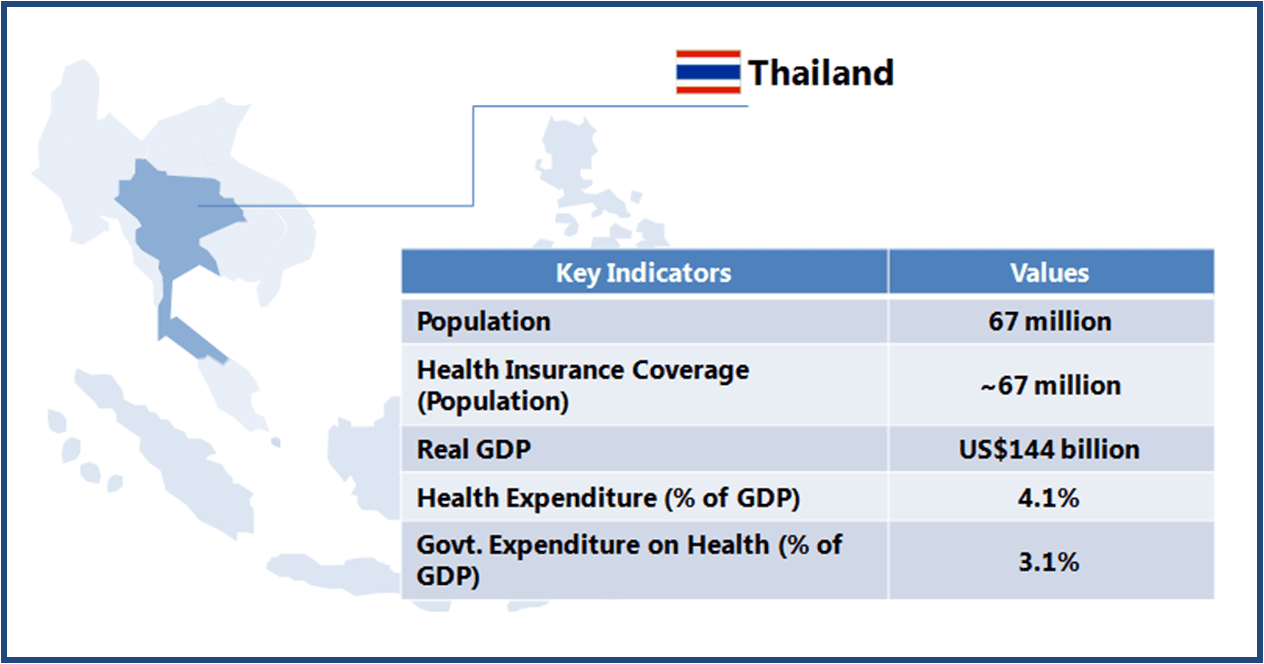

Thailand boasts of world class medical facilities (especially in the private healthcare sector), and is among the world’s largest medical tourism markets. The government is looking to further develop Thailand into an “International Health Center for Excellence” under its second strategic five-year plan (2012-2016).

Thailand boasts of world class medical facilities (especially in the private healthcare sector), and is among the world’s largest medical tourism markets. The government is looking to further develop Thailand into an “International Health Center for Excellence” under its second strategic five-year plan (2012-2016).